Uncovering How Faults and Mobile Shale Control Methane Seepage in the Gulf of Mexico

New research from Tulane University is reshaping scientific understanding of how methane escapes from the seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico. A master’s thesis by Walee Yeboah, a recent graduate of the Department of Earth and Environmental Science, reveals that active faults and mobile shale structures beneath the seafloor play a critical role in directing methane and fluid migration—challenging long-standing assumptions that salt tectonics alone dominate seepage patterns in the region.

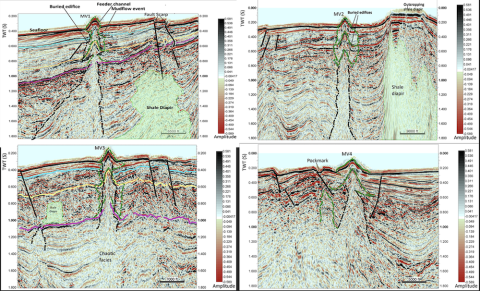

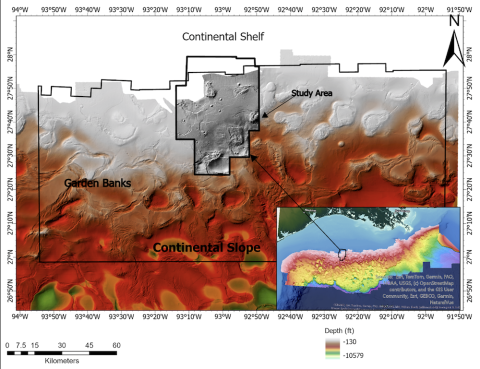

Yeboah’s thesis, “Relationship Between Seepage Features and Subsurface Structure in the Garden Banks Region of the Gulf of Mexico”, combines 3D seismic data with high-resolution bathymetry to examine the geological mechanisms controlling seafloor pockmarks and mud volcanoes. His analysis documented linear alignments of pockmarks directly above fault scarps, providing evidence that recent fault movement opens pathways for fluids and methane to rise from deep, overpressured layers to the seafloor. The research also identified buried mud volcano complexes, revealing episodic eruption cycles that span thousands to millions of years.

These findings have important implications for climate science. Methane is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide during its first two decades in the atmosphere. While recent studies have shown that oil and gas operations in the Gulf of Mexico emit significantly more methane than previously estimated, Yeboah’s work emphasizes the importance of understanding natural seepage contributions in order to accurately assess total emissions. His research demonstrates that methane release is governed by active geological processes rather than passive leakage alone, providing a framework for distinguishing natural sources from industrial ones.

The study also carries significance for offshore safety and infrastructure planning. The Garden Banks region lies within one of the most productive offshore energy basins in the United States, where drilling platforms, pipelines, and other infrastructure coexist with complex subsurface geology. By identifying fault-controlled fluid migration zones, the research offers insights that are critical for assessing geohazards and informing safer offshore development and pipeline placement.

One of the study’s key contributions is its recognition of mobile shale diapirs as major drivers of persistent mud volcanism, expanding scientific understanding beyond the traditional focus on salt domes. This finding has global relevance for other passive continental margins where similar subsurface structures may influence fluid flow and methane seepage.

Yeboah’s thesis was approved by his committee—Dr. Nancye Dawers, Dr. Keena Kareem, and Dr. Jamiat Nanteza—and highlights Tulane’s leadership in Gulf of Mexico geological research. By applying advanced seismic interpretation techniques to a region of high environmental and industrial importance, the work underscores how geological processes operating over long timescales can have immediate relevance for climate research, natural hazard assessment, and energy infrastructure planning.

As attention continues to focus on methane emissions and offshore development in the Gulf of Mexico, this research provides a timely, science-based perspective on the subsurface geological controls that govern when and where methane is released from the seafloor.